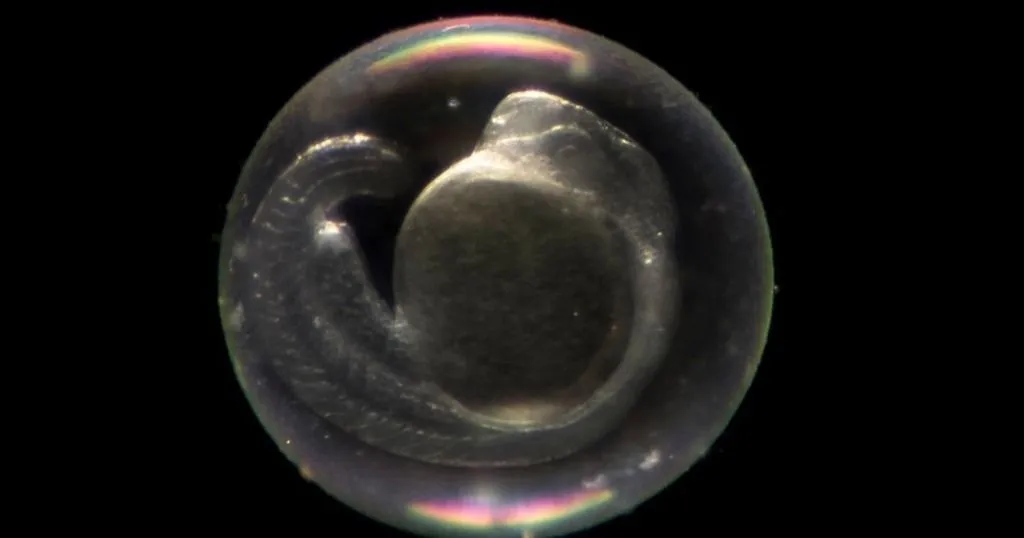

Isolated and stressed zebrafish as a model for major depression

Depression: a fifth (!) of us cope with it, making it the most prevalent psychiatric disorder. Prof. Gerlai recently investigated the interaction between mild stress and developmental isolation in zebrafish models.

Posted by

Published on

Thu 09 Mar. 2017

Topics

| Depression | EthoVision XT | Video Tracking | Zebrafish |

Depression: a fifth (!) of us cope with it, making it the most prevalent psychiatric disorder. It comes as no surprise that researchers try to wrap their minds around it, not to mention the interest gained from the pharmaceutical industry.

How to model depression

Depression is not easy to model in animals, as we cannot really determine if a rat has low self-esteem or if a zebrafish is suicidal. But that doesn’t mean researchers haven’t found other behaviors to characterize depression-like symptoms in animals, and several – sometimes very successful – models have been developed to study this disease.

How does one get depressed? “Life stress” is a well-known factor in the development of depression (Hill et al., 2012). In animal research, this is mimicked by “Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress” (UCMS). Another factor is early life adversity, such as abuse or neglect – in animal research, they use "developmental social isolation".

Better characterization

While zebrafish proved to be a suitable model for both paradigms (UCMS and social isolation), the interaction between the two is not clear. The lab of Prof. Robert Gerlai recently investigated this interaction and aimed for a better characterization of both behavioral and neurochemical changes in zebrafish. (Fulcher et al., 2017)

Rearing and stressors

To characterize these changes, the researchers exposed both socially reared fish and fish reared in isolation to UCMS. The stressors included partial exposures to air due to lowered water levels, tank changes, net chasing, complete elevation from the tanks, water replacement, and individual restrainment.

In addition, two groups of fish (one reared socially and one reared in isolation) were not exposed to UCMS. This way, the researchers could determine the sole effect of early life adversity.

Novel tank testing

For behavioral testing the fish were placed in a novel tank, which in itself is a known stressor. Behavior was automatically measured for 3 minutes using video tracking (EthoVision XT). Turn angle, distance traveled, freezing, and distance to the bottom were used as a measure of anxiety-like behaviors.

Shoaling to video screens

To measure shoaling (social) behavior, the fish were exposed to video images of 5 conspecifics projected on two screens on either side of the tank after being in the tank for 10 minutes. The distance to the screen, also measured with video tracking, was also used to measure shoaling.

Stress increases anxiety

Being exposed to UCMS increased anxiety-like behavior in the zebrafish. Developmental isolation alone did not have this effect. It also did not decrease the distance of the fish to the screens while they were exposed to conspecific images, suggesting they did not decrease their shoaling behavior. It did have other effects on their behavior, though. For example, they traveled a larger distance.

UCMS also decreased dopamine and serotonin levels in the fish, but only if they were reared in isolation.

Different effects

Both the social isolation during development and the exposure to mild chronic stressors have their behavioral effects. While the latter seems to increase anxiety in the fish, the first mainly affects motor responses.

Weight gain and neurochemical changes show an effect of the exposure to UCMS, but only in fish reared in isolation.

A combination for the best model?

This study shows that to model depression in research, a combination of developmental isolation and exposure to mild stressors seems useful.

References

Fulcher, N.; Tran, S.; Shams, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Gerlai, R. (2017). Neurochemical and behavioral responses to unpredictable chronic mild stress following developmental isolation: the zebrafish as a model for major depression. Zebrafish,14(1), 23-34.

Related Posts

Inhibitory avoidance learning in zebrafish (Danio rerio)

Zebrafish behaviors shows true effect of chemicals on aquatic animals