What, Why and How to learn in a museum

Although children can learn a great deal on their own, conversations with parents have a big influence on the content, recall and transfer of what they learn.

Posted by

Published on

Tue 29 Dec. 2015

In the Netherlands we have a so called “museum card” which allows you to visit museums for free. In the last few years I visited quite a few of them together with my children. In Amsterdam we saw the ‘Nachtwacht’ in the Rijksmuseum, did science experiments at Nemo, and learned about how the sea has shaped our Dutch culture at The National Maritime Museum.

We have also visited the ‘Openluchtmuseum’ (Netherlands Open Air Museum) in Arnhem several times, because this one is the closest to us. At this museum you can learn a lot about how people lived in the past, and the objects they used for cooking their meals, brewing beer, doing the laundry, and so on. Each and every time we visit this museum, my children and I discover new facts. It’s a great learning environment, but what do my children actually recall of these many museum visits?

Natural setting for research

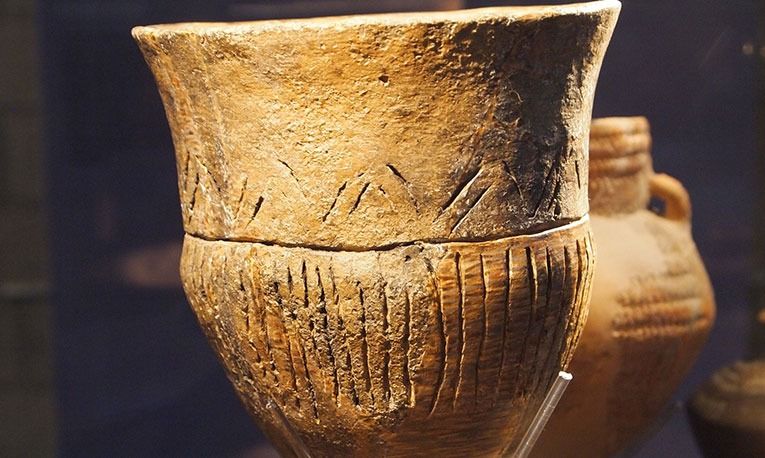

Researchers from Loyola University Chicago also chose a museum as the setting for their experimental and observational research. In two museum exhibits, they examined the effects of parent-child conversation and object manipulation on children’s learning, transfer of knowledge, and memory of the exhibit. Many studies of learning and parent-child interaction have stressed the need to observe informal learning in natural settings; an exhibit designed specifically for children is therefore ideal for this research. Specifically, hands-on activities in the room represented the daily practices of the Pueblo people 800 years ago.

What influences children’s learning in a museum?

To examine the influences of conversation, they created a set of conversation cards about objects in the Pueblo exhibit. On one side of each card was a picture of one of the objects, on the other side were questions that invited parents and children to talk about the object pictured on the card.

In particular parents’ open ended questions (e.g., What, Why and How – the Wh-questions) could make sure that children focus on relevant aspects of an exhibit object or activity, and elicit information from children to diagnose what they do (and do not) know. Children and their parents were randomly assigned to receive these conversation cards, the physical objects themselves, both, or neither, before their exhibit visits.

Coding behavior

The study consisted of several activities: the pre-exhibit activity where the parent and child did or did not receive the cards and/or the target objects, visiting the exhibits, filling in a family questionnaire, and recalling at home (optional). Parents were asked to recall the visit with their children 1 day and 2 weeks following the museum visit.

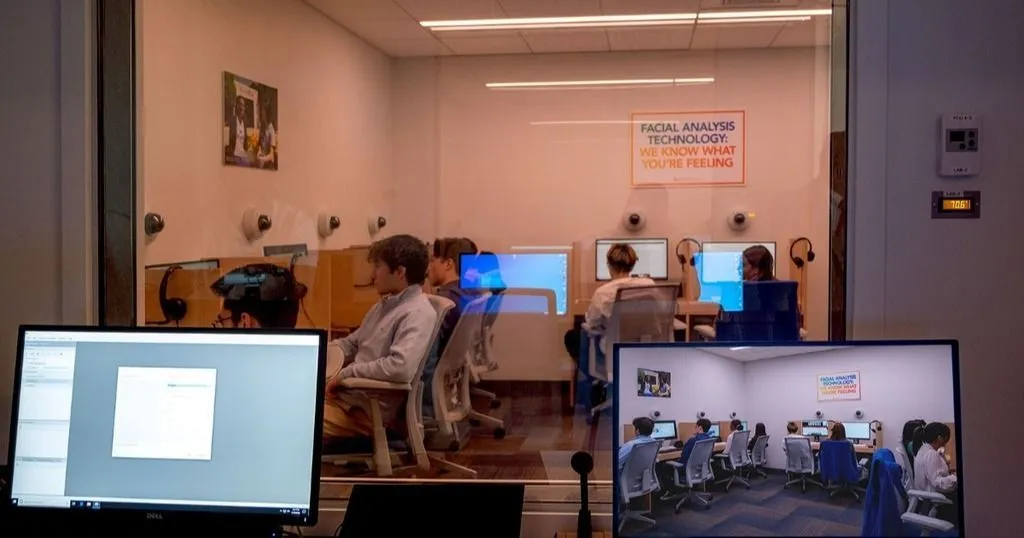

Verbal and non-verbal behaviors were videotaped during the exhibit visits and at home, and coded using The Observer XT. The researchers focused on the parents’ elaborative talk by defining the total number of Wh-questions and prior knowledge associations, children’s responses to parents’ Wh-questions and also their spontaneous talk in the Pueblo exhibit and nonverbal behavior. They also assessed information about transfer of information across the two exhibits and from museum to home.

Intervention results in more parent-child joint talk

The researchers found that the conversation cards did influence parents’ conversations and actions in the exhibit. As predicted, the cards appeared to cue parents to talk in more elaborative ways and enable children in more spontaneous talk. They engaged in more joint nonverbal activities with the objects than children and parents who did not receive the cards. Also families transferred more information between the two exhibits if they had received the cards.

In conclusion, the researchers state that learning from direct experiences with objects and learning through conversations with others are intertwined. Although children can learn a great deal on their own, conversations with parents have a big influence on the content, recall and transfer of what they learn. Wh-questions focus a child’s attention on aspects of an event and help determine the parent what the child does know and does not know. So now I know even better how to engage with my children during our next museum visit, to best enhance long-term retention of the information we learn!

Reference

Jant, E.A., Haden, A., Uttal, D.H. & Babcock, E. (2014). Conversation and Object Manipulation Influence Children’s Learning in a Museum. Child Development, 85 (5), 2029-2045.

Related Posts

5 Tips for writing better Horizon Europe grant proposals

Behind the Scenes: Human Behavior Research Labs